Today, we are talking with Christopher Fleet, Map Curator, and Katie Haffie, Community Data Harvester, about a three-tiered crowdsourcing maps project that has just kicked off at the National Library of Scotland. We discuss the mechanics of data harvesting, the importance of inter-organizational collaboration, and the challenges and rewards of planning volunteer-based projects that are both enjoyable and of practical use to the extended community.

(Archivoz) Can you talk a bit about the role of Community Data Harvester? What sort of work does this position entail, and why is it important? Why did you feel such a person would be of benefit to the National Library of Scotland?

(Christopher Fleet and Katie Haffie) The Community Data Harvester role involves both gathering data and expanding our audiences. Primarily, the role is directed towards gathering and creating spatial data relating to the Library’s digital map collections. Our collections represent a huge repository of Big Data, but we are still at an early stage in extracting and re-using this data. So, our transcription projects embrace the wide and growing corpus of people who are highly engaged with historical maps and keen to devote time to gathering data about these maps. Being community-focused, the role is also designed to provide advice and support to the public through resources like workshops and online research guides. Last month, we held our first workshop on re-using our georeferenced maps and released an online guide. Through these events, we look to expand accessibility and encourage further digital engagement with our collections by equipping users with the tools to develop their GIS skills, further their research (be it personal, professional or academic) and access valuable historic maps from Scotland and beyond.

(Archivoz) Your new project is divided into three sub-projects. Can you tell us a little about each of them?

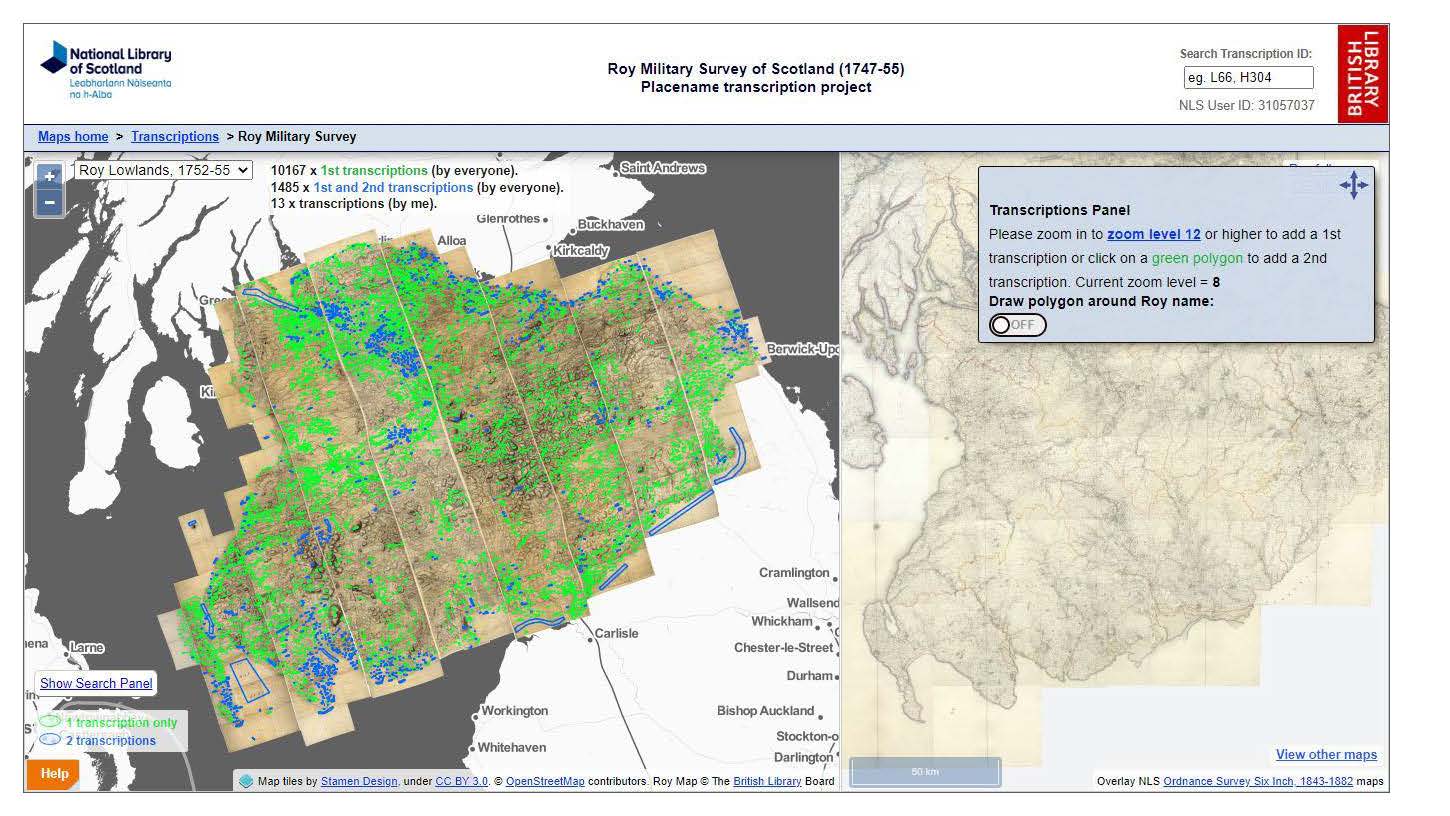

(C.F. and K.H.) The first is our Roy Military Survey of Scotland Placenames Project which got underway at the end of February in collaboration with the British Library (who hold the original Roy mapping). For this project, we recruited volunteers to transcribe all the placenames from the Roy Military Survey of Scotland maps (1747-1755) and they are off to an amazing start, recording over 30,000 transcriptions in only two weeks.

Known to its contemporaries as the ‘Great Map’, the Roy Military Survey of Scotland is not only strikingly beautiful but also uniquely important to Scottish history and map-making. It is the only standard topographic map prior to the Ordnance Survey in the 19th century. For many Highland areas, it is the most detailed and informative map that survives for the entire 18th century. The project uses a simple interface to draw boxes around names on the Roy map and transcribe placenames, linking where possible to later forms of the name on the Ordnance Survey maps. We are on the way not only to creating a very powerful way to instantly locate places on Roy’s Map, but also to presenting online for the first time around 6,000 names that hitherto have been inaccessible to online researchers. The resulting gazetteer will be released as a dataset for onward use on the NLS Data Foundry and the BL Research Repository. And, for the likes of Scottish family or local historians, this new gazetteer will be of huge value, quite apart from its utility for other types of landscape and placename studies.

Our next transcription project is in partnership with the rights of way and access society Scotways. This time, we will ask volunteers to trace the routes of footpaths from the Ordnance Survey’s 6-inch to the mile maps, dated around 1900. The point locations of over 12,000 “F.P.” footpath abbreviations have already been identified, but the routes of the footpaths on the ground have not yet been traced. So, our Scotways Historic Footpaths Project will identify these footpaths and make them available as an open layer, to help facilitate Scotways’ work in researching the backgrounds of footpaths today and safeguarding them as rights of way.

Last but not least, we have our Ordnance Survey Edinburgh 25-inch Transcription Project, run in collaboration with the Machines Reading Maps team at the Alan Turing Institute. For this project, our volunteers will transcribe all of the text on the Ordnance Survey’s 25-inch to the mile mapping for Edinburgh (1890s). Including street names and a wealth of related urban information, the OS 25-inch mapping is the most detailed scale covering all of Scotland’s inhabited regions. The project will use a simple interface to draw boxes around names on the 25-inch mapping, transcribe the text and tag or categorise it following a simple set of terms. The results will be released as an open dataset for onward use, allowing new search possibilities for street-names and related map features. The transcribed written content will also be used as a test dataset for machine learning approaches to identify text on maps, which are being actively developed. If successful, we hope to extend this project geographically, beyond Edinburgh, using this method of mapping.

(Archivoz) Each of the sub-projects is being run in tandem with other organizations: one with the Alan Turing Institute, one with Scotways—an organization dedicated to protection of public rights of access in Scotland—and one with the British Library. How were these partnerships established, and why is this sort of cooperation useful?

(C.F. and K.H.) First of all, each of the partners with whom we are collaborating are able to offer good advice and support on the practicalities of the project. For example, Scotways has unrivalled expertise on footpaths, their representation on maps, and legal issues relating to rights of way. Although we can clearly find and identify footpaths, there are some dilemmas over interpreting quite where footpaths started and ended and their advice on this has been extremely helpful. Amongst other things, the Alan Turing Institute is well versed in machine learning techniques and visual recognition of features and placenames on maps using Artificial Intelligence. The Edinburgh 25-inch project is using an interface and related tools that will directly support machine learning techniques, a subject which NLS is less able to take forward directly on our own.

Also, these collaborations lend credibility to the projects. For example, the British Library is a widely respected institution, it is the holder of the Roy Map, and its support for the project adds integrity and trustworthiness to the work itself. Those giving their time to trace footpaths will appreciate Scotland’s leading right-of-way institution’s direct involvement in the work, and that the resulting dataset will directly feed into and support that group’s valued work to preserve footpaths and recreational access to the outdoors.

A third advantage of these collaborations has been access to each institution’s different publicity channels, which has allowed us to reach different audiences and helped to ensure recruitment of sufficient numbers of people for successful outcomes.

(Archivoz) Why have you chosen crowd-sourcing as a tool? Can you unpack some of the mechanics of the situation for us—means of advertisement, training protocols, possible challenges you may encounter as you roll out the various stages of the project?

(C.F. and K.H.) As mentioned previously, there is a large and growing number of people who are highly engaged with historical maps. We enlisted their help via a sign-up webpage advertised through our website, Maps Twitter, NLS Twitter, NLS newsletters and CAIRT newsletter. Using volunteers, we can extract information from our maps that are beyond the resources and responsibilities of Library staff. We have been very keen to choose projects that would not have been done by Library staff, as the aim has not been to duplicate work or replace the work of staff with volunteers, but rather to do things that have been beyond the scope of the Library’s work so far. We are very grateful to all of our participants for their interest and contributions to the projects. Our hope is that the projects will provide an enjoyable way for participants to interact with historic maps, whilst also engaging in a useful activity that will produce long-term benefits. We have tried to find projects that fit with these twin aims of enjoyment in doing the work itself, and for all involved to appreciate the value of the end result. This has also involved trying to create easily understood tasks and user-friendly interfaces, with an overall scope that is not too daunting – the right size and level of complexity.

(Archivoz) What sort of benchmarks have you set for yourselves? The project is just beginning; in an ideal world, what is the outcome you’re hoping for? How will you determine whether the project has been “successful”?

(C.F. and K.H.) Each of the projects has quite clear outcomes based on definite targets. For example, the Roy Military Survey map and the Edinburgh Ordnance Survey 25-inch projects aim to transcribe all of the place names from these maps. The interfaces that we are using make it quite clear when a name has been transcribed, as it will have a coloured polygon around it. As the project progresses, it will become steadily harder to find any names without polygons, at which point the projects will effectively be complete. With the Scotways footpaths project, the location of ‘F.P.’ abbreviations are already known and represented by green dots on the map, and the project will invite volunteers to trace the route of the footpath by following these abbreviations. Over time, it will become steadily harder to find any ‘F.P.’ abbreviation not attached to a traced footpath. We also hope to use spatial queries to identify any ‘F.P.’ abbreviation without a corresponding footpath.

Whilst these are obvious targets that can measure “success” in terms of dataset completeness, it is actually far more important for us that the participants enjoy the projects and feel them a worthwhile use of their time. These are new map crowdsourcing initiatives for NLS, so an important related aim is for us to build knowledge and experience as to which aspects of the project have worked well so we can learn from these in the future. The three interfaces will use related but different technologies, and we also hope to learn which of these works best to better plan future projects. For example, how important is it for users to be able to edit their own transcriptions after completing them, and how important is it to allow others to do this? The balance between simplicity and complexity for the interfaces and workflows will be interesting to test in practice.

(Archivoz) Beyond its benefits to the Library itself, what is the importance of involving the community at large in projects like these? What do you hope your volunteers will learn from the process, and what do you hope to learn from them?

(C.F. and K.H.) Engagement with the broader community is a key strategic target for the NLS. Our 2020-2025 strategy is entitled ‘Reaching people’, and this is taking place through a number of related activities, both physical and online, recognising that there are always new ways to connect communities with Library collections. Whilst we already know that our maps website is popular and highly appreciated, regularly receiving over 10,000 user visits every day, these transcription projects will offer a new type of engagement. Through asking people to focus on specific details of these maps – such as place names or footpaths – and to gather other useful information about these features, we hope to inspire them to examine and study the maps in new ways. As a result, they will hopefully come to understand and appreciate these maps better. We hope that in some cases it may also make users more informed and appreciative our maps.

The Library will also benefit from this collaboration, gaining insights into our users and their interactions with the maps. This could be quite a straightforward—for example, which characters are difficult to transcribe or which features are trickier to interpret. Volunteers’ priorities and progress will be useful elements to monitor. Which geographic areas or types of feature are targeted first, and why? How important is it for those involved to connect with each other as part of an online forum or community? How important is it for those involved to see their own progress and how important is competition (for example, leader boards) as part of the broader collaboration? To what extent are challenges that stretch the knowledge and experience of those involved useful, and to what extent are repetitive, relatively simple tasks acceptable? We will also gain useful knowledge of what kinds of staff resources, such as time and expertise, are required to sustain the project, and how to keep the group motivated as the projects progress.

Images courtesy of the National Library of Scotland

Christopher Fleet

Map Curator, National Library of Scotland

Chris Fleet worked at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and the National Library of Wales before joining the National Library of Scotland in 1994. His main responsibilities at NLS relate to modern and historical digital mapping, and making historical maps available online. He has researched, written and spoken widely on these subjects, and is a co-author of several popular books on Scottish mapping, including Scotland: Mapping the Nation (2011), Edinburgh: Mapping the City (2014), Scotland: Mapping the Islands (2016), and Scotland: Defending the Nation (2018).

Katie Haffie

Community Data Harvester, National Library of Scotland

Katie Haffie joined the National Library of Scotland in 2021, having previously worked for the National Trust for Scotland and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Working as a Community Data Harvester, Katie’s role involves hosting workshops, creating online guides and running data gathering activities. She provides audiences with support and advice to access and use our map collection, whilst offering opportunities to engage with historical maps.