The Bates County Historical Society & Museum is located in Butler, Missouri along the western border of the state, about one hour south of Kansas City. It was established in 1961 and is celebrating 60 years of keeping the stories of her people alive and well.

In 2021, Missouri celebrates 200 years of statehood and Bates County marks the 180th anniversary of its founding. Another date of enormous significance was April 15, 1861, the day the American Civil War officially began. The Civil War fanned the flames of circumstances set in motion years earlier during the bloody Border War of the 1850s. Infamous characters like William Clarke Quantrill, Jesse and Frank James, Cole Younger, Bill Anderson, and a host of other outlaw guerrillas were born out of the fiery War of the Rebellion. To many Missourians, both before and after the War, these men were heroes, but to understand why they were so highly regarded, one must look back to the beginning. While Kansas bled, Missouri burned, giving birth to a hatred that ran deep, often lasting for generations. Some folks swear it lingers still.

“Martial Law,” by George Caleb Bingham, depicting the forced evacuations under Order No.11.

Four counties along the Missouri and Kansas border became known as “The Burnt District” in August 1863 when Union General Thomas Ewing issued the infamous General Orders No. 11. Citizens were ordered to vacate their properties, and failure to do would result in imprisonment or death. Most of the region’s men were gone. Some were in hiding, forced to leave their families in order to survive; some who had suffered losses had become hard-hearted killers; still others had joined either the Confederate or Union armies. In addition, livestock, wagons, carts, food, and other supplies had been ‘foraged’ by both sides, leaving civilians with barely enough to survive. Life at home had been difficult at best, but life after expulsion, on the road traveling to unknown destinations, proved to be pure hell. Descriptions of the forced evacuation refer to the women, children, and elderly seeking refuge somewhere—anywhere—outside the district as pitiful, dreary, hopeless, dirty and thirsty.

After commandeering anything left behind, the Union troops torched towns, homes, barns, and the winds of the heartland swept the fires across the prairie until there was little to nothing left in a radius of approximately 2200 square miles. The Federals had hoped this scorched earth policy would break Southern sympathies and discourage guerrilla groups, but the resilience, determination, and downright stubbornness of the people in western Missouri came as a shock to the military commanders. Their brutal tactics had not stopped anything.

Bates County was ground zero of Order No. 11. Since the other three counties had garrisons of Union soldiers in various locations, people could present a petition to the military requesting permission to stay in the town. However, there were no Federal troops in Bates County, so it holds the dubious distinction of being the only county in America’s history to be forcibly depopulated and completely destroyed. From issuance of the order in 1863 until a county court was finally able to gather and meet in 1866, no county business was conducted. It is estimated that less than 30% of the property owners returned to the county following the war, and those who did return owed three years’ worth of back taxes. County infrastructure was destroyed. Diaries and letters noted that the land had been taken over by wolves and rattlesnakes. Seventy percent of the 893 square miles of Bates County was now available for sale, and sell it did. An unprecedented wave of land speculators, businessmen, mining companies, railroad entrepreneurs, settlers, shopkeepers, skilled craftsmen, and workers swept into the county, essentially disinheriting those who had originally settled the land. The discovery of rich coal deposits in the southern half of Bates County attracted industrial ventures, and Reconstruction went into high gear. The last operating coal mine in the state of Missouri was located in the southwestern part of Bates County; it closed at the end of 2020.

Several years ago the University of Kansas and Missouri partnered together to host an annual Archaeological Field School in Bates County. For two weeks, students lived at the Museum while sifting through a designated dig-site known to have been burned during Order No 11. Their search for artifacts is not so different from a historian’s search through old books and papers, seeking to unearth vital pieces of information that will help to solve a puzzle.

Bates County Museum

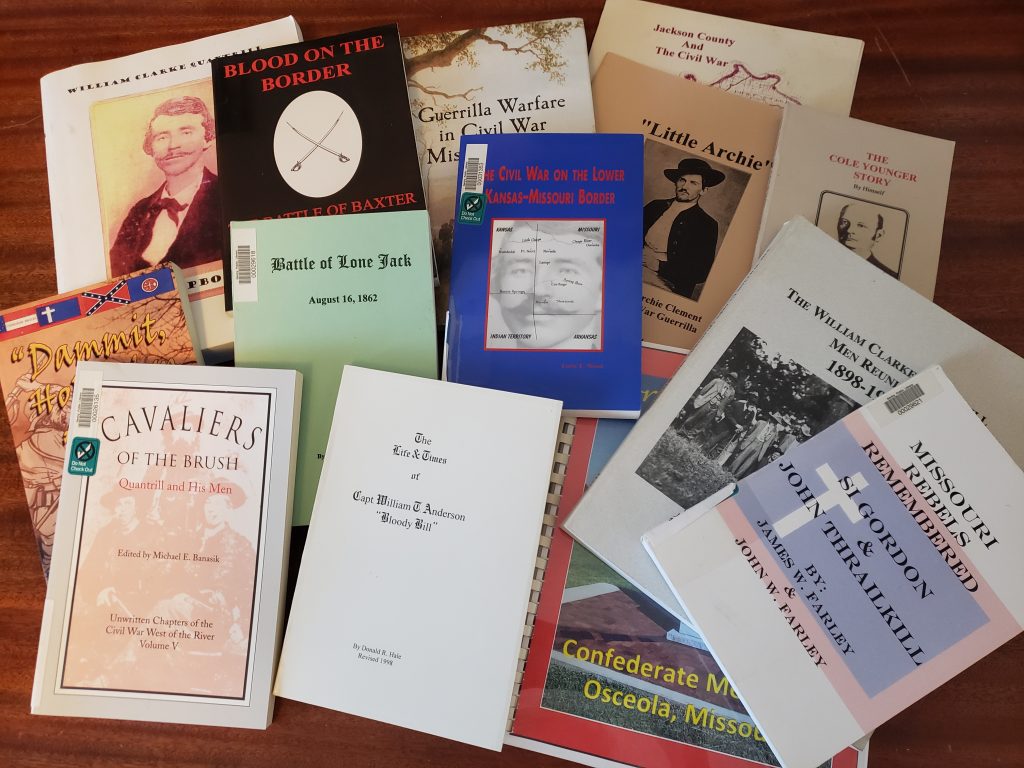

At the Bates County Museum, our motto is Preserving Our History & Sustaining Our Heritage. Over the last few years, fulfillment of that motto has led to the establishment of a Border War, Civil War, & Guerilla Warfare Research Library that includes published works, regional accounts, reminiscences, diaries, stories, newspapers, family histories, articles, artifacts, and more. Stories of the victorious are eagerly preserved but stories of those who have been defeated are often dismissed or even intentionally silenced, but the recollections of both sides are critical to a comprehension of the complexities of war, particularly when that war is waged against civilians. Political views, greed, personal vendettas, revenge, and the inevitable deterioration of humanity all add to the suffering in the midst of war. It is imperative these remembrances be recalled, recorded, examined, and understood if we, as a people, are to continue moving forward together from rebellion to reconstruction and ultimately to reconciliation. Saving the history and stories of western Missouri during those volatile years is now an ongoing mission of the Bates County Museum, and support for the project has been extraordinarily enthusiastic.

The Border War, Civil War & Guerrilla Warfare Research Library contains well over 500 books, research papers, videos, maps, military rosters, and various other materials and newly arriving contributions keep adding to the scope of the collection. Many of the books and memoirs were written and published in western Missouri. They were written primarily for friends and family, along with a few hardcore civilian historians, so printings were limited. As the years have gone by they’ve become scarce, often completely lost.

In 2020, two important collections were received. The Museum now houses the Quantrill Special Collections Research (QSCR), a body of material collected over several years. The Quantrill collection, which had most recently resided with the Benton County Historical Society in Bentonville, Arkansas, has now returned to Missouri. Also in 2020, a founding member of the William Clarke Quantrill Society passed away and his family donated his very substantial private collection to the Museum.

The Bates County Museum views the opportunity to preserve these materials as a privilege, knowing that future generations will have access to these often obscure writings in years to come. Visitors are spellbound by stories about the colorful characters who have called Bates County home. There are heroes and heroines among their number, scoundrels and soiled doves, the pious and the humble, the proud and the pitiful—but the most exciting characters of them all lived in the county during the Border War, the Civil War, and the years of guerrilla warfare. These stories have survived the tests of time and are worthy of preservation.

Images

Image 1 – United States Library of Congress Digital Collections.

All other images by permission of Peggy Buhr and the Bates County Historical Society & Museum.